Sep 2020 - Mar 2021

user experience

videography

Tsailu Liu

Kahren Kersten

Kennedy Liggett

Rachel Thomas

Joseph Rogers

Use behavioral science and design to inform and improve five North Carolina county governments’ COVID-19 responses.

In September 2020, I was contracted to work as a designer on an experimental project that would attempt to improve five North Carolina county governments’ COVID-19 responses. The project was scheduled to end in March 2021—giving us 6 months to create as positive of an impact as possible. Knowing COVID would expand well beyond those 6 months, it was our goal to arm the counties with the tools they needed so they could continue their efforts long after we had left. When we began in September, a vaccine was but a distance dream, but in December, when vaccination was no longer a possibility, but a reality, we switched our efforts to focus purely on the vaccination journey.

(Continue scrolling to read more about our exploration, and where we ended up.)

Selected as a winner of GDUSA’s 2021 Health & Wellness Design Awards.

Awarded a $75,000 grant for COVID-19 by the University of North Carolina System.

I began by meeting with the project heads and learning who I would be working with, along with which aspects of COVID-19 our project would focus on. In short, our team would consist of five North Carolina county governments, 12 behavioral scientists from Duke University’s Center for Advanced Hindsight (CAH), a professor of psychology from Lenoir-Rhyne University, and five designers from North Carolina State University—which is where I fit in. And throughout the course of the project, we would be focusing on three work streams: Masks & Distancing Compliance, Vaccine Adoption, and Combatting Misinformation.

We then began gathering as much information as we could. I attended weekly meetings with the county employees to discuss the challenges they were experiencing. CAH created several literature reviews and conducted an exploratory study with North Carolina residents to understand their attitudes on COVID-19. We also interviewed several North Carolina residents to gain an even greater understanding of their COVID-19 perceptions.

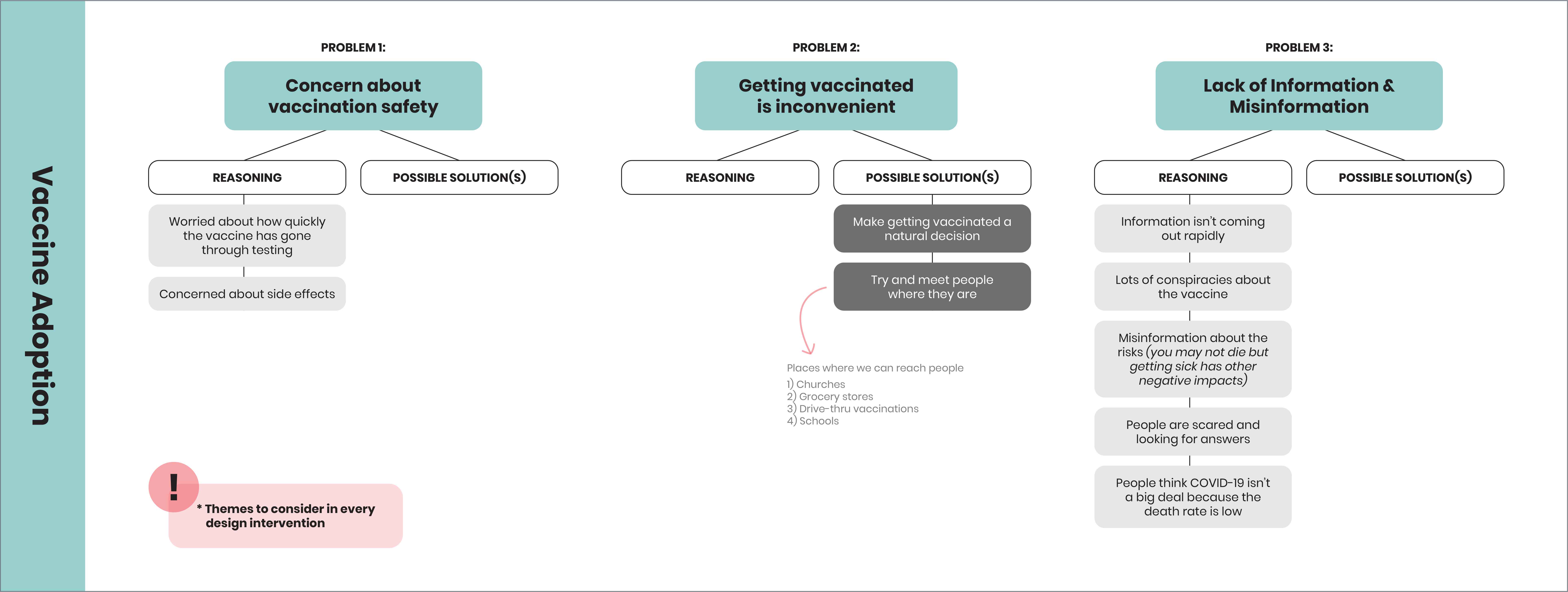

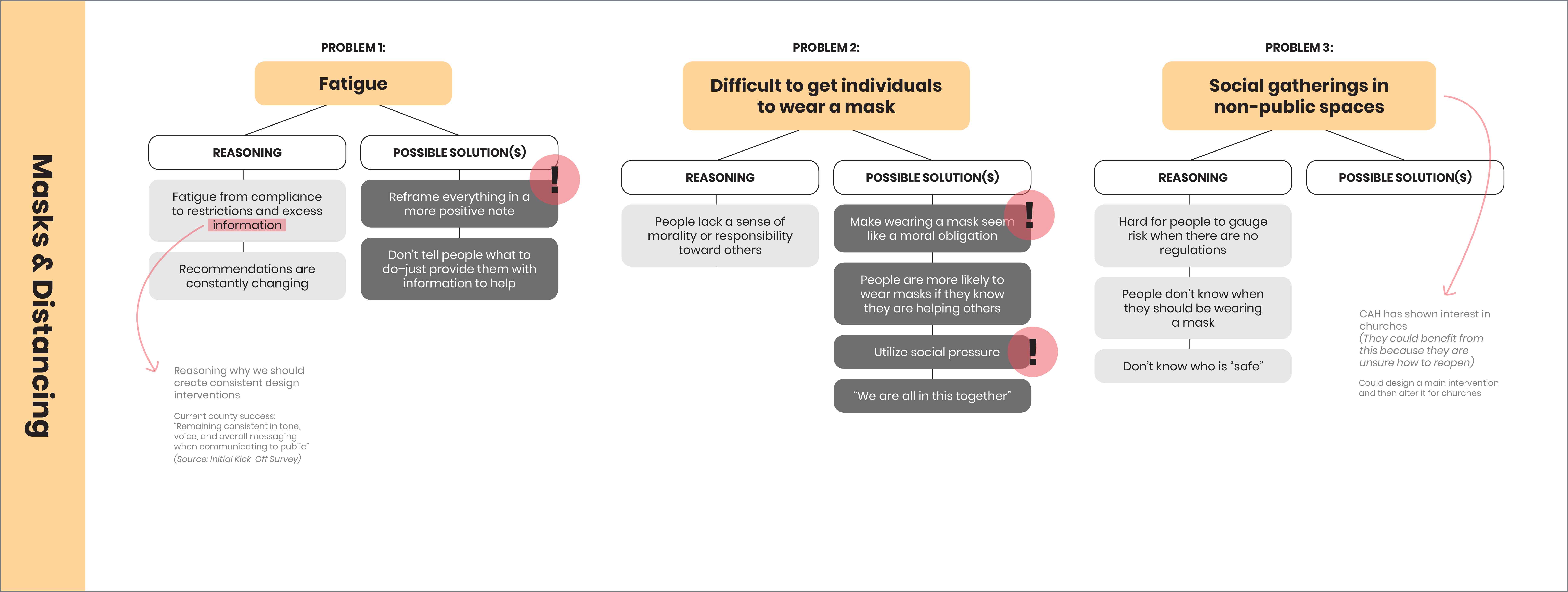

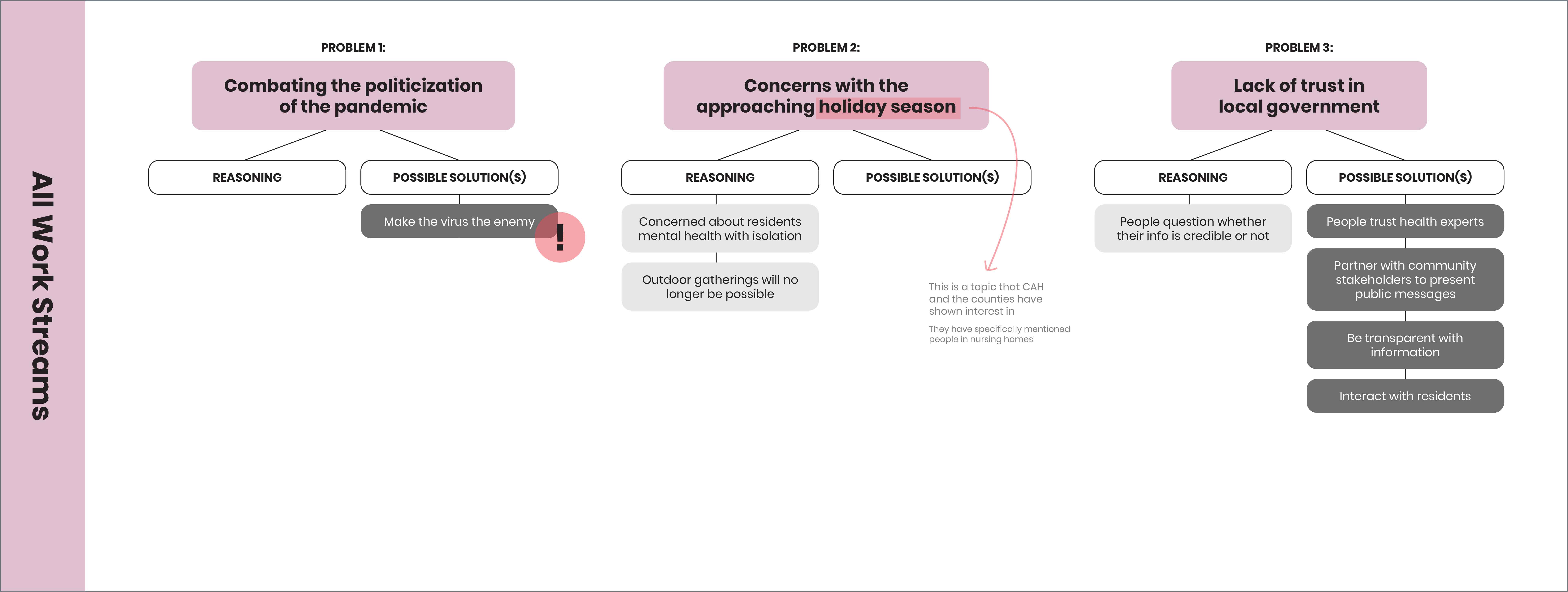

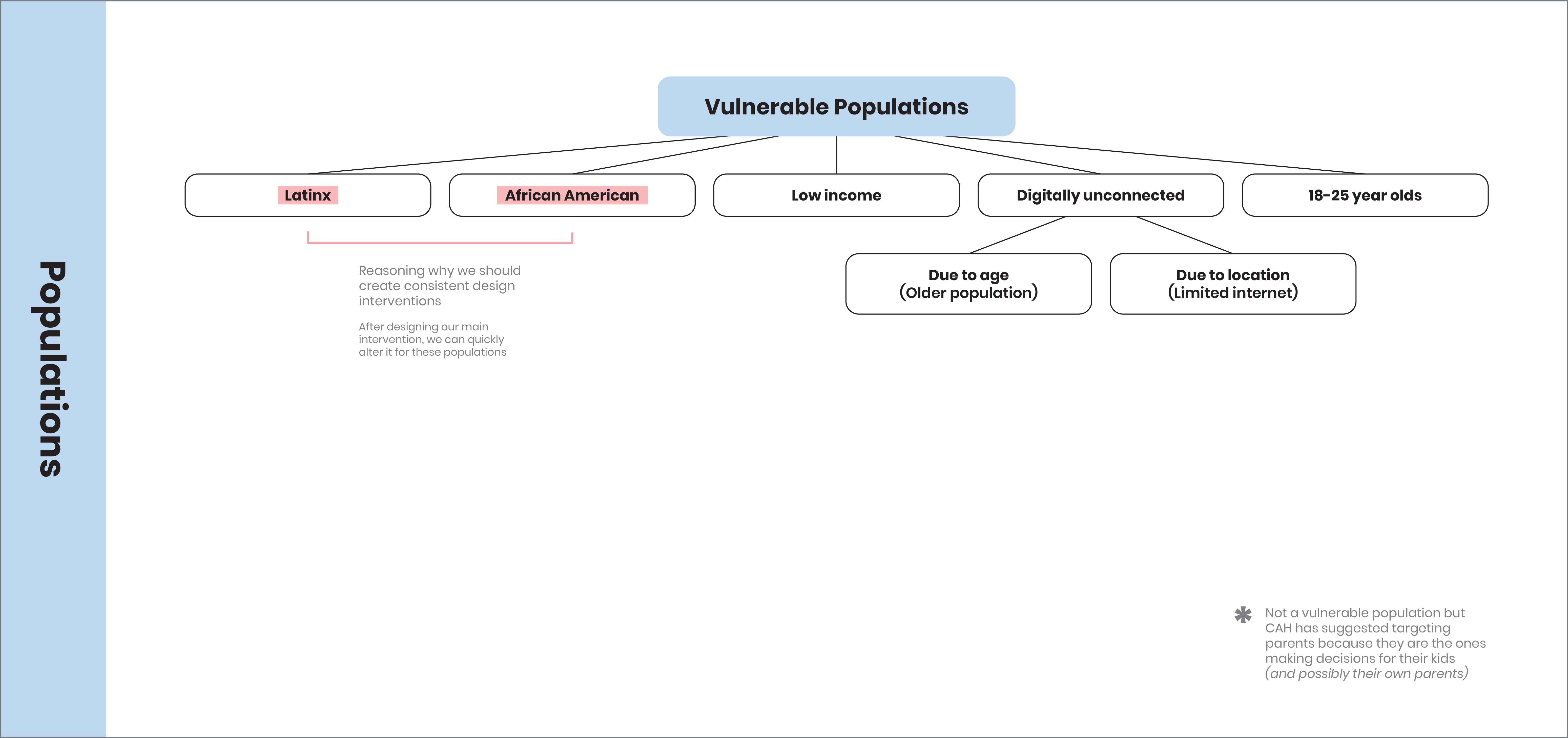

I then analyzed all the information we had gathered and created a map illustrating the most prominent problems in each work stream, as well as methods that could be used to combat them. I also identified the most vulnerable populations when it came to COVID-19 information and resources. (Swipe left to learn more)

Before we began developing ideas, we wanted to test people’s reactions to different messaging techniques and visuals. The first study we conducted tested people’s willingness to adhere to safe behaviors for altruistic reasons. We did so by creating ads for an app the State was currently promoting called SlowCOVIDNC. Within these ads, we tested messages that called on altruistic motives versus ones that did not, and studied how those messages influenced people’s willingness to download the app. We also wanted to test which visual messages were most compelling, so some people received the State’s text-only ads, some received our illustrative ads, and others received our iconographic ads.

After testing 695 participants, we found that altruistic messaging was more persuasive than non-altruistic messaging. We also found that the illustrative ads were the most persuasive visually.

In October 2020, at the beginning of flu season, we conducted a study to test the persuasiveness of potential vaccination campaigns. Since flu vaccines were relevant at the time, and a COVID-19 vaccine had yet to be approved, these campaigns revolved around increasing people’s willingness to get their flu shot. Our plan was to take the results from this study and apply it to COVID-19 vaccination messaging once a vaccine was available.

After testing 1,896 participants, we found that all five campaigns performed equally low when it came to persuasiveness. We concluded that if people had hesitancies towards the flu vaccine, they were going to have even more hesitancies when it came to COVID, and if we wanted to persuade people to get vaccinated, we would need to understand their reluctance more.

At this time, we were nearing December, and the winter holidays were quickly approaching. This was an area of great concern for the counties, so we put everything else on hold and quickly created an intervention that would encourage people to stay safe during the holiday season. We knew people were going to gather and celebrate the holidays regardless, so our plan was to acknowledge this fact, while showing people how they could do it safely.

After the holidays, we reset and decided to focus all our efforts on vaccination. At this point, we had an overwhelming amount of research floating around our Google Drive, so I created a brainstorming activity where we could compile everything we knew about the COVID-19 vaccine. Within this activity, we looked at specific population’s hesitancies, as well as the problems and opportunities within each step of the vaccination process.

We then identified the populations that were the most hesitant towards vaccination, as well as the steps within the vaccination process we wanted to impact. At this point, vaccination rollout had just begun, and we knew our contract would end before the vaccine reached the general public; so we decided, based on our resources, that we could make the most impact when it came to the first step of the process, and the last.

To impact the first step of the vaccination process (People hearing about the vaccine) we created a series of videos that were designed to promote vaccination and ease people’s hesitancies. The first video we created gave people an inside look on how the COVID-19 vaccine was developed. This video was designed to address women, conservatives, and people of color—all of which had concerns about the vaccine’s safety and speed. (All three videos were developed by the NC State design team and animated by PNTA)

The second video we created painted people who get vaccinated as heroes—specifically mothers who do so to protect their family. This video was targeted towards women, who were found to be more hesitant towards vaccination, but also the most influential when it came to the rest of their family getting vaccinated. If we could get women on board, research showed their family would follow.

The third video we created showed the COVID-19 vaccine as the next step towards getting back to “normalcy.” This video was targeted towards conservatives, who were found to be less likely to get vaccinated, but adamant about getting their freedom back. Conservatives were also found to be more opposed to vaccine messaging, so this video didn’t center around vaccination like the other two.

With all three videos, it was our goal to make the content reflective of what was happening in the counties we were serving, as well as rationalized by the research we had done.

While working with the counties, they emphasized how important and underserved their Latinx populations were, so we prioritized making these videos in Spanish so we could properly serve this audience.

We wanted the videos we created to reach as wide of an audience as possible, but we knew that due to the limited time the counties had, they would only be able to spread these videos so far. To combat this, we utilized some grant money we had earned to pay for our videos to appear across Facebook and Google's ad network. Additionally, we, alongside NC State’s communications agency, geotargeted the ads to only show within the five counties we were serving. And within that, we targeted the ads to specifically appear to the people we had identified as the most hesitant towards the COVID-19 vaccine.

Combined, across Facebook and Google, our ads had 626,777 impressions. Our ads performed exceptionally well on Facebook, averaging a 62.5% view through rate—surpassing what Facebook benchmarks as a good view through rate by 30%. Unfortunately, our ads didn’t perform as well on Google, but they did average a view through rate that was close to what Google benchmarked as ‘good.’ (In the diagram below, each square represents 1,000 people)

To impact the last step of the vaccination process (People sharing their experience with others) we created a series of promotional items that people could receive after getting their COVID-19 vaccine. We wanted to create items that people would proudly wear and share with others, so we played on our findings from our study about altruistic motives and adopted the tagline, “I GOT MY COVID VACCINE TO PROTECT NC”— eliciting people’s willingness to do something for the wellbeing of others.

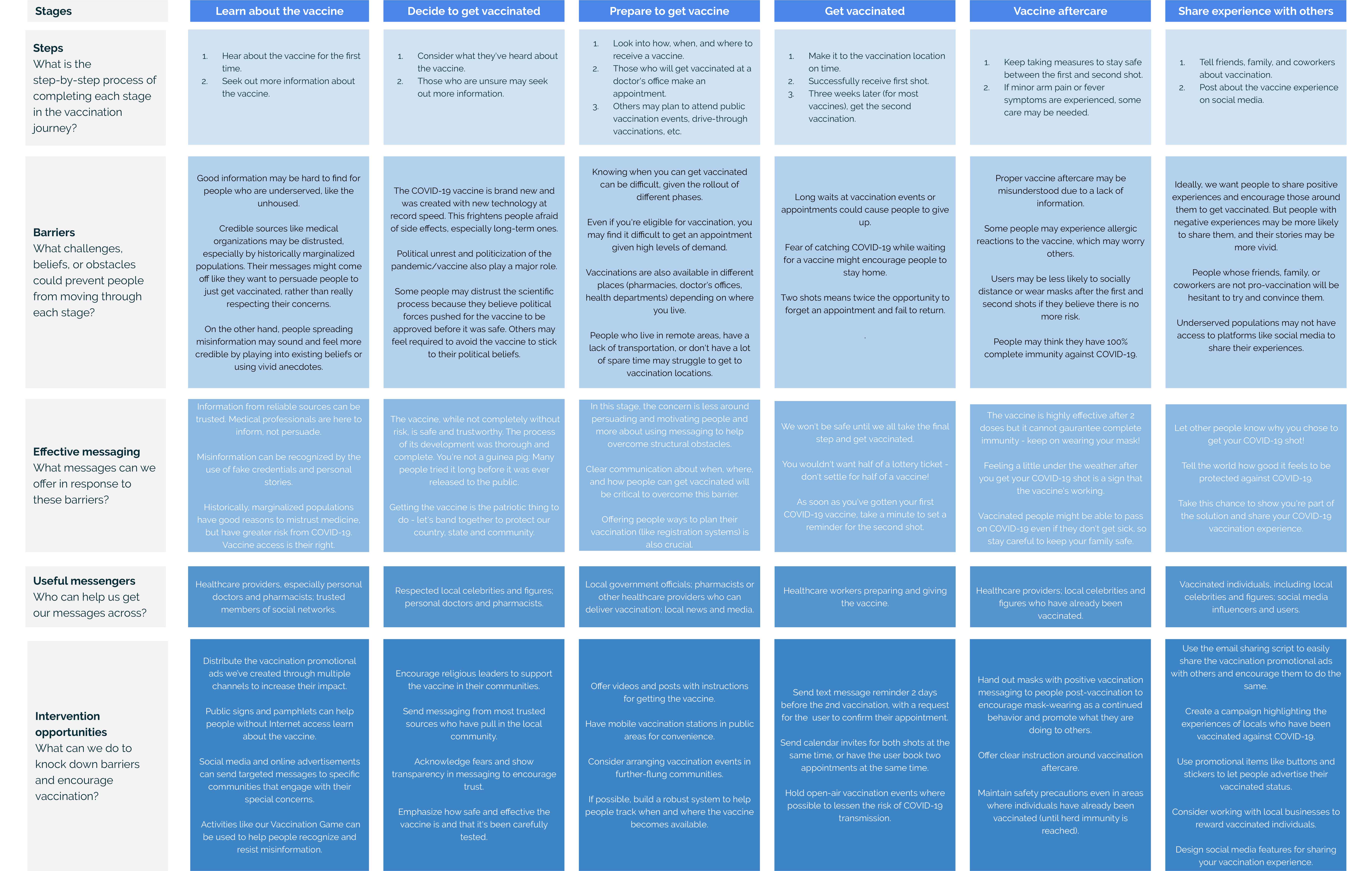

In March, we came to the close of our project, but we knew the counties’ problems with vaccination were far from over. To help them continue their efforts, we provided them with an experience map that detailed each step of the vaccination process and what barriers they may face, as well as effective messages and interventions they could utilize to combat those barriers.

(If you would like to learn more about this project from a behavioral science perspective, please check out CAH’s report.)